At The New York Times on Monday, columnist Li Yuan describes how, as "wages stagnate and jobs disappear, the promise of upward social mobility is eroding, especially for those from modest backgrounds. For many […], the Chinese Dream no longer feels achievable." Similar themes have featured prominently on CDT in recent months, from uproar over the "4+4" fast-track for medical qualifications to commentary on the decline of former "golden ticket" degrees like computer science and the resurgent appeal of official careers. Other examples include gallows humor comparing young jobseekers with Terracotta Warriors and citing the Chinese people’s capacity for hardship as a trade-war superweapon. (As Li notes, similar frustrations are widely felt elsewhere.)

A recent essay on the WeChat public account 老干体v adds to the growing body of online writing on economic precarity and gloom in China. The author notes troubling signs in key economic indicators, arguing that the rich are subject to the whims of the powerful, while ordinary people either sink or swim depending largely on chance.

The lower bound of Jiangsu’s benchmark coal price recently dropped 22% month-on-month, and 24% year-on-year!

Can it be that this resource-poor country’s chronic energy shortages are finally behind us?

According to former Premier Li Keqiang’s economic analysis, electricity consumption and freight volume serve as the two leading indicators of economic development, the barometer and thermometer of the nation’s economic activity, directly correlated with the rise and fall of GDP.

Does this mean we’re now on a trajectory of declining power consumption and economic contraction?

In fact, it’s not just electricity prices that are tumbling: in the last few years, glass has fallen from 3,300 yuan to 987, lithium carbonate from 230,000 to below 60,000, coking coal from 3,400 to 760, rebar from 6,200 to 2,900 …

Some might wonder whether lower prices aren’t a good thing. If that’s you, don’t bother to read on.

The trend in power consumption was obscured last year by sustained 6.8% growth, and the China Electricity Council predicts 6% growth this year as well, breaking through the 10-trillion kilowatt/hour mark.

But the rate of growth is slowing, for the first time since the [COVID] masks came off—the power consumption index is again showing signs of "irregularity" following its [post-pandemic] return to a normal growth trajectory.

Breaking down the power consumption, industry used 49.7% of the total, but its consumption increased only 5.1% from last year, well below the overall increase of 6.8%.

This year’s projected 6% overall increase will likely be held back again by lagging industrial power consumption.

This way of looking at it clarifies a number of points.

We’ve grown so accustomed to constant growth that we don’t believe that housing prices could fall, or that investors could actually pull out over safety concerns.

Electricity is inextricably linked to coal. Back in the ’90s, some mineshaft engineers from Wenzhou’s Cangnan and Pingyang counties were hired to sink shafts in Shanxi Province.

Once the mines were up and running, the engineers were given ownership as payment, because coal prices at the time were low.

So when we entered the WTO in 2001, the economy soared, power consumption shot up, coal prices exploded, and these coal bosses became the big winners behind the "electricity tigers."

I once went to Shanxi to meet a coal baron who spat right onto the restaurant’s red carpet. When it was time to settle up, he handed over two bricks of 10,000 yuan bills, still wrapped from the bank, and asked if that would cover it. Anything left over, he said, they should keep as a tip.

Then the industry was abruptly nationalized in the 2008 coal reforms, for safety and other reasons. Prices were unilaterally set by officials, with only a small portion paid up front, and the remainder was indefinitely deferred.

This disaster crushed the Shanxi coal bosses’ dreams—they still prefer not to talk about it.

Of course, more unforgettable still is the photo of grass sprouting on the Bund that was shared online on April 9, 2022.

There was even one video of a pack of stray dogs sniffing around the broad street in search of food.

At that point they thought, like some enterprises, that once the masks came off, the horses would still run and the dancers would keep dancing, just as they had before. [A reference to Deng Xiaoping’s promise of continuity in post-handover Hong Kong.]

But I felt even then that once things relaxed, we’d see the truth.

One acquaintance of mine, a state-owned enterprise boss who was "sent inside" a while ago, once objected to my pessimistic outlook while we were chatting at his place.

There’s a line from Shaanxi opera: "Fate throws misfortune at madmen, like bricks at mad dogs." This is as true for officials as it is for the rest of us. The authorities are finally unable to keep up the game they’ve been playing until now.

On the evening of November 28 last year, there was a "Shanxi Night" reception in Hangzhou to attract investors from Zhejiang. According to public reports, of course, this was a big success, but the rumor was that while the leaders were giving their speeches onstage, the entrepreneurs below grew ravenous. Some tried to pinch some hors d’oeuvres, but were tackled by servers who said "the leaders haven’t started eating yet!"

I could hardly breathe for laughing when I heard this: "The leaders may have changed, but the bosses who got screwed last time are still around!"

The other day, a relative of mine in Shanghai mentioned that commercial rents on Qipu Road have dropped to 500 yuan a month from a peak of 70,000.

She said it will never hit that level again.

My blood ran cold.

Weeds grow on every grave; it’s those left behind who feel this as an affront.

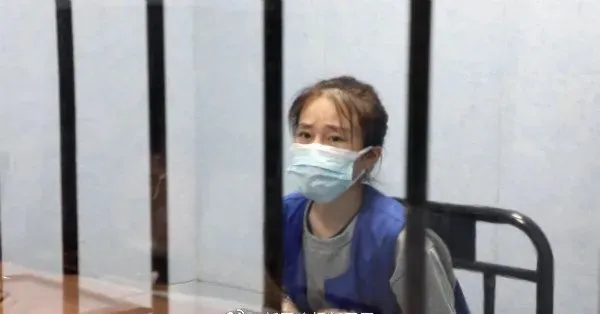

Thinking back to those few years, there was a milk tea shop owner in Shanghai who started doing explicit livestreams [literally "large-scale" livestreams, a censorship-evading euphemism] to pay the rent, and was sentenced to three years.

Everyone’s memories of the Three Years of Masking will differ, but for me, this photo of her made a deep impression. Every time I look at it, I almost can’t breathe.

Because that time was also when our editorial department was under the heaviest financial strain. My hair turned grey overnight—if there’d been the slightest interruption to our money flow, we’d all have been out of work.

I had a little more luck than that small business owner, but that I’m the one who made it through is just a matter of survivorship bias.

That three-year sentence will be over now, though I don’t know if she’s free or not.

But either way, her milk tea shop is probably long gone.

That was the life and livelihood she once dreamed about.

It was also the broken dreams of all the rest of us.

I’ll never be able to forget the look in her eyes through those iron bars. After the rumbling flood passes, all you can do is stare at the crushed rubble of the life you’d painstakingly built. [Chinese]